K Practice of Dowa Education Today

4 Dowa Education as Human Rights

In this section we briefly describe the Burakumin's educational conditions and educational efforts to improve these conditions after the Second World War.

JAPANESE SCHOOL SYSTEM AFTER THE SECOND WORLD WAR

As we have already seen in PART I, educational policies adopted by the Japanese Government before the Second World War attached considerable importance to equal opportunity and fair competition within the school system. This policy inclination was succeeded by the post-war government and several reforms were made to further promote equal opportunity. The length of compulsory education was extended to nine years; six years of primary education and three years of secondary education. The complicated system of secondary schools was streamlined into a simple high school system and higher education opportunity was enlarged.

As better educational achievement has already been the major means of social mobility, the enlargement of educational opportunities resulted in an immense "education fever" among people. To meet the boiling demand for educational opportunity, the government spent large sums on school resources and also many private facilities were built. The high school enrollment rate rose, exceeding 50% in 1955 and 90% in 1975.

Higher education enrollment rate exceeded 20% in 1964 and reached almost 40% in 1975. This educational explosion dramatically enlarged the middle-class population and raised the standard of socio-economical status.

BURAKUMIN'S EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT LEVEL AFTER SECOND WORLD WAR

In spite of the explosive enlargement of educational opportunity, the Burakumin's educational attainment level after the Second World War remained low. Table 1 compares the school backgrounds of Burakumin and the whole population in Osaka Prefecture for each generation.

It may be easily inferred that unenrollment or a drop-out from primary education heavily concentrated among Burakumin before the Second World War. For those aged 60 or over, 20% of Burakumin were not enrolled in or dropped out of primary education, whereas for the counterpart the figure was less than 1%. This pitiful situation of Burakumin can not be observed for those aged 20-29, but the relatively low educational attainment level for Burakumin can be found in other figures. The percentage of those who completed junior high school is 20.8% for Burakumin and 7.3% for the counterpart. Also, we can find considerably lower figures for Burakumin in higher education levels.

This lower educational attainment of Burakumin inevitably leads to lower socio-economic status, especially in a society like Japan that has a social mobility system heavily dependent on schooling. Indeed socio-economic status level itself is considerably low for the Burakumin, although their lives are supported by special governmental measures.

TABLE 1

School Backgrounds of Burakumin and the Whole Population in Osaka Prefecture

| School Background | Age | |||||||

| 60 or over | 40 to 59 | 30 to 39 | 20 to 29 | |||||

| Buraku | Whole | Buraku | Whole | Buraku | Whole | Buraku | Whole | |

| Primary School Uncompleted | 18.7 | 0.7 | 6.5 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Completed Junior High School | 69.9 | 49.2 | 71.3 | 30.0 | 33.7 | 11.2 | 20.8 | 7.3 |

| Completed Senior High School | 9.6 | 37.8 | 18.4 | 50.7 | 45.8 | 47.5 | 57.4 | 51.4 |

| Completed Junior College | 1.0 | 5.1 | 1.6 | 5.5 | 10.6 | 14.9 | 13.7 | 22.7 |

| Completed College or Over | 0.8 | 4.8 | 2.1 | 11.6 | 9.5 | 24.1 | 8.0 | 16.8 |

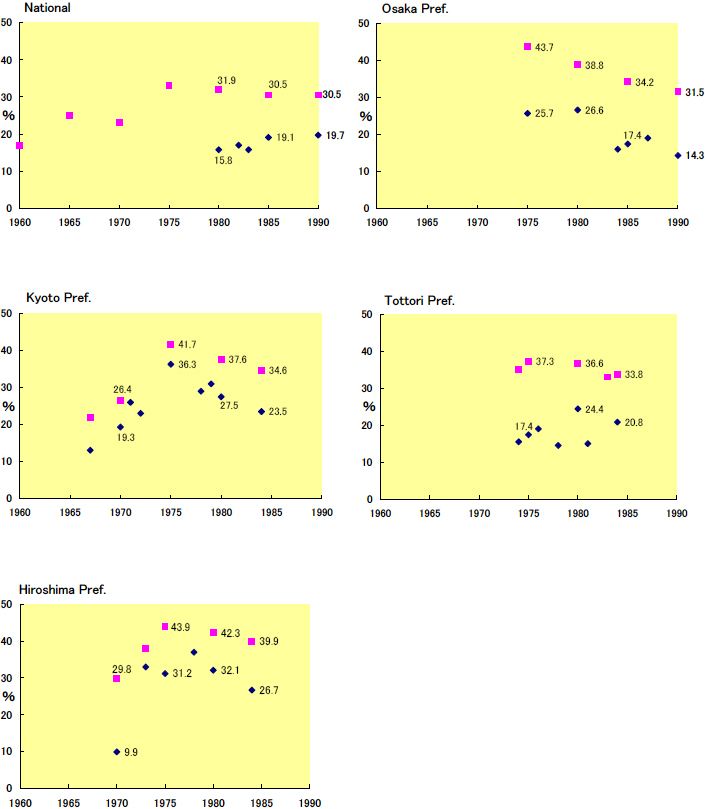

Figure‚P High School Entrance Rates of Burakumin and the Whole Population

Let us look more closely at the Burakumin's educational attainments. Figure 1 shows national and prefectural senior high school entrance rates for both Burakumin and the whole population.

In 1960, the figures show that the rate for Burakumin was approximately 30%, whereas it was approximately 60% for the counterpart. In 1975, high school entrance rates for the whole population reached around 9O% and, without exception, large gaps that had existed in 1960 narrowed to between 2- 10 points lower figures for Burakumin. Some people interpret this rapid closing as success in mainstreaming the Burakumin and consequent success in improving Buraku pupil/students' scholastic ability.

However, that was not the case. According to research on Buraku pupil/students' scholastic ability conducted in the post-war period, nearly 1 standard deviation difference in achievement scores was found between Burakumin and non-Burakumin pupil/students regardless of when and where the research was conducted. This meta-analysis on Buraku pupil/students' scholastic ability leads us to conclude that the relative difference in scholastic achievements between the Burakumin and non-Burakumin pupil/student has been maintained to a considerable degree through the post-war period

Supposing that achievement scores follow normal distribution, it can be estimated that 1 standard deviation difference between the two groups' achievement score distribution will lead the lower group's entrance rate to 15% when it is 50% for the whole population, and 85% when it is 90% for the whole. These hypothetical calculations agree with statistics (see Figure 1), which means that the relatively rapid rise in Buraku students' high school entrance rate observed in the period of 1960-1975 does not mean real improvement in Buraku pupil/students' scholastic ability nor success in mainstreaming Burakumin.

Since 1975 the government has kept the high school entrance rate at 90-95%, while the Buraku students' rate has been consistently lower by 2-10% (see Figure 1). This curious phenomenon is understandable by assuming a consistent difference in the scholastic achievement level between Burakumin and non-Burakumin.

Figure 2 College Entrance Rates of Burakumin and the Whole Population

The difference between these groups in college entrance rates is much larger (see Figure 2). As college entrance examinations require a much higher academic standard, this significant gap again suggests a consistently lower achievement level of Buraku students.

It is true that the absolute level of the Burakumin's educational attainment has risen in the post-war period but as the analysis above shows, the relative level has remained considerably low for Burakumin, reproducing Burakumin's relatively lower socio-economic status. Overall enlargement of educational opportunity does not necessarily result in the improvement of minority group status. This fact presents a serious question to the modern notion of equality that regards equal opportunity as a sufficient condition in assuring equality. What we need now is to find out precisely what conditions would stimulate the Burakumin's motivation toward learning more and what would accelerate the improvement of the Burakumin's achievement level. It is obvious that the success in attaining these goals depends heavily on the effort to transform the Buraku children's learning process.

Also, it must be recognized that Dowa education has not been quite effective in this regard. Though the practices of Dowa education have been conducted in many regions and schools for nearly half a century, Buraku children's educational attainment has not improved, as we have already seen. The fundamental issue indicated by this fact is that macro-level improvement is not observable despite hard efforts and many micro-level improvements attained by Dowa education. In the following, we will look at what Dowa education has been practicing till today in order to change the conditions of the Buraku children's learning process.

MAKI NG BURAKUMIN CHILDREN STAY IN SCHOOL

The first problem that Dowa education confronted was the absence of Burakumin children from school. The saying "That child is absent again today" was shared among teachers who took Buraku children's massive unenrollment or long-term absence seriously. These teachers started to visit the Burakumin community frequently and persuaded to send their children to school or encouraged children themselves to come to school.

Frequent home visits became one of the routine practices of Dowa education. Its aim was mainly to gain the Burakumin's trust of schooling and to understand each child's background in order to ensure effective instruction.

Through these home visits, a lack of money to buy textbooks or other necessary supplies was reported by many teachers, eventually resulting in free textbook distribution and other treatment by the government. Also, in some prefectures additional teachers started to be assigned to schools with Buraku children to support additional activities of teachers for Buraku children. This special assignment is called "Dowa kahai". These efforts resulted in the gradual decline of the unenrollement rate and long-term absence rate of Buraku children.

Following these special educational benefits such as scholarships for high school and national governments were established. Strong requests for such measures to the local and national governments were made by Burakumin themselves in the late 1950s, represented by the demand of the Buraku Liberation League. Political power relations between Buraku movements and local governments create a considerable variety of government policies. In some regions, Buraku children are suffering from lack of basic educational resources even today.

However, we have to be careful in assessing the efficacy of these government measures on Buraku children's educational attainment. As we have already seen, we cannot observe real improvement in the relative achievement level of Burakumin at the macro level. It is obvious that these government measures did not have an overall influence on Buraku children's educational attainment, though it had quite a strong influence at the micro level (i.e. increased school enrollment).

COMMUNITY ACTIVITIES

Buraku children's absence from school gradually declined during the 1950s and early 1960s. Buraku children were now present in school but still not ready to learn. They couldn't concentrate on learning and misconduct was frequently seen among Buraku students. Traditionally, Japanese teachers have treated student misconduct with reprimands or punishment, but this method usually aggravated the Buraku students' distrust of teachers and the school because of their internalized sense of alienation. Some teachers began to understand this sense of alienation and underlying perception of discrimination as well as poverty, and tried to speak with Buraku students on their concerns in order to gain their confidence. Understanding the sense of alienation of minority students and students in difficulties is now widely recognized as the core philosophy in Dowa education.

Misconduct was just among the outlying cases of general difficulties of Buraku children in the classroom. To manage the generally lower achievement of Buraku children, some teachers started to give extra instruction to Buraku children out of school, usually using facilities in Buraku communities. These activities are called "chiku-shinshutsu gakushu," meaning community outreach instruction.

Along with these instructions in Buraku communities by teachers, some Buraku communities began to form children's organizations to keep children out of trouble, wake up Burakumin consciousness and provide recreation opportunities for the children. School teachers and college student volunteers usually supported these activities. In some cases, outreach instructions were integrated into the organized community activities of Buraku children. As most of these children's organizations were established under the influence of the Buraku liberation movement, they are usually named "Kaiho Kodomo-kai" meaning community-based children's liberation organizations.

Facilities and staff for this kind of educational instruction is now partly financed by the government. Few local governments have their own community education systems, including special facilities and staff.

SCHOOL AND CURRICULUM REFORM

The Dowa education practices we described above are mainly intended to control the Buraku children's environment of schooling and learning. Although they are necessary conditions for educational equality, they do not constitute sufficient conditions. To assure effective learning by Buraku children, the schooling and learning process themselves must be reconstructed

In Japanese schools, instruction is usually given to a class of 30 to 40 pupils/students by a single teacher in a single sequence. Mastery learning conscience is shared among Japanese teachers but the above conditions pose difficulties in setting the pace of instruction. This always results in some students remaining behind; usually Buraku children. Those schools with a heavy enrollment of children with difficulties, mostly schools with Buraku children, also have most of the classes staying behind the standard. (Standards are prescribed in "GAKUSHU SHIDOYORYO' meaning government guidelines for teaching.) In these cases, extra curricular instruction is usually given to those children few hours a week. Extra curricular instruction is called "SOKUSHIN" in Dowa education, meaning "to hasten or to promote." The kind of outreach instruction we have seen before can be regarded as a kind of extracurricular instruction specifically given to Buraku children.

Providing extra care to children in this way has been inefficient however. For many children it was a mere extra burden and often resulted in cooling their aspirations. Also, it made many of them passive about learning.

In the late 1970s, a few schools with Buraku children started a new instructional reform called "HAIRIKOMI SOKUSHIN." Utilizing "DOWA KAHAI" (extra teachers) who had been free from their former task of ensuring Buraku children's presence at school, they assigned extra teachers in the classroom to assist the main teachers, chiefly taking care of those children who were considerably behind the standard in understanding the current curriculum.

It may have been easier to divide the class according to the degree of progress but this method was not adopted initially. Dowa education practice had been deeply influenced by the Soviet collectivism-oriented education that attached greater importance to collective harmony than to individual success. Thus, under this ideal, any action that seemed to split class unity was carefully avoided. Physically splitting the classroom was out of the question. However, HAIRIKOMI SOKUSHIN was obviously insufficient to compensate for lower achievement. Dowa education gradually moved toward splitting the class and paying the closest care not to hurt children who were placed in lower achievement classes, and not to disintegrate classroom identity and harmony. This was called "CHUSHUTSU SOKUSHlN." CHUSHUTSU means extraction or pull-out.

Recently, new challenges toward this problem are taking place. One of them is called "KOBETSUKA" which means individualization. Utilizing overall resources in schools such as teachers, time, space, educational programs, worksheets and media, KOBETSUKA attempts to prepare the most appropriate learning settings for each child, centering around an individualized program of study. Distribution of such resources is planned to maximize the achievement of children who are behind the standard and not to discourage children who are going ahead. Collective classroom activities are also carried forward eagerly. This new set of practices is influenced by the concept of the effective school movement that was initially established by Ronald Edmonds's research on school effectiveness on minority and poor children in the United States. Considering the consistently lower achievement level of Buraku children, reforming schools and curricula is now among Dowa education's major agenda.

However, these practices to ensure better scholastic achievement among Buraku children do not take place in many schools because of a lack of understanding of the seriousness of the situation of Buraku children.

ABILITY FOR LIBERATION

Scholastic ability has been consistently discussed in Dowa education from the very beginning. Many teachers thought that competition based on scholastic achievement was a major source of discrimination, and therefore held negative feelings about scholastic ability itself. Through this argument, the notion "KAIHO NO GAKURYOKU" was established, meaning "ability for liberation," namely the ability of children to know what discrimination is, to point out the problem, and to fight social inequality. There are some variations on this notion; regarding scholastic ability and ability for liberation as contradictory to each other and regarding the former as the basis for the latter. In some cases, few teachers and/or activists strongly oppose any kind of school practices aimed at improving scholastic ability, giving this notion as a reason for opposition.

This notion, posing serious questions about uncritical acceptance of achievement-orientation, was shared by many people especially by minority groups. Indeed the side effects of achievement-orientation such as "diploma disease" are not ignorable and will continuously be one of the main issues of Dowa education.

AFFIRMATIVE ACTION

In many countries, affirmative action has been adopted by many schools as a mean s to raise minority status and also to make school environment multi-cultural.

In Japan, this notion of affirmative action is regarded negatively by school administrative authorities because, as they argue, it would seriously harm the fairness of entrance selection. The only case of affirmative action in an educational facility implemented so far is one by the Shikoku Gakuin University, which adopted this policy for Burakumin and Koreans in Japan starting in April 1995. This test case is expected to stimulate attention about affirmative action.

The Dowa education movement has also been playing an important role in abolishing discriminatory employment practices. Until recently, instrumental discrimination such as inquiring about applicants' birth and parentage in application forms and/or in interviews was customary in the private sector. To protect minority students from these forms of discrimination, the Dowa education movement had fought intensively against these employment practices and achieved considerable improvement. For instance, a standardized format of application forms has been set up without columns for birth place, parentage, or any other information that would possibly lead to discriminatory employment practices. These forms are not yet applied to college graduates, and several other means are still used in excluding Buraku applicants. These activities can also be regarded as education as human rights.